6 Critical Press Brake Technical Specifications: The Ultimate Selection Guide

Table of Content

This post is also available in:

Español (Spanish) العربية (Arabic) Русский (Russian)

Investing in a CNC press brake is a transformative decision for any fabrication shop. However, for many buyers, the technical parameter table feels like a wall of data rather than a helpful tool. To ensure a high ROI and avoid costly equipment mismatches, you must look at Press Brake Technical Specifications not as isolated numbers, but as the boundaries of your production capability.

This guide decodes these essential parameters from a customer’s perspective, explaining what each value means for your business and how to use them for precise machine selection.

1. Nominal Pressure: Matching Tonnage to Material Reality

In the world of metalworking, Press Brake Tonnage is your “force ceiling.” It represents the maximum pressure the cylinders can exert. When a buyer looks at this figure, the primary question should be: Does this accommodate my toughest material?

Selection logic dictates that you cannot rely on mild steel charts alone. If your shop is moving toward Stainless Steel 304 or high-strength alloys, your required pressure increases significantly—often by 50% or more for the same thickness. To protect your hydraulic press brake from premature wear, never buy a machine that perfectly matches your thickest part; instead, select a tonnage that provides a 20% safety buffer above your most frequent Bending Force Calculation.

Press Brake Tonnage Calculator

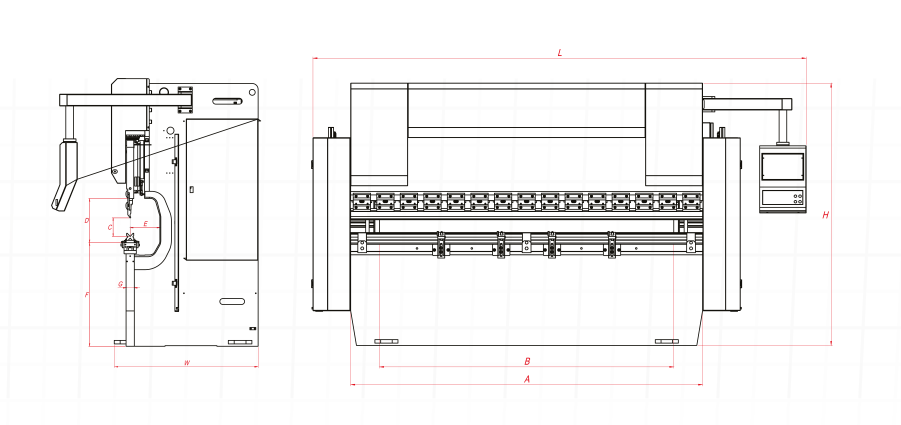

2. Table Length vs. Distance Between Uprights: The Pass-Through Logic

Many customers mistakenly believe that the Max Bending Length is the only horizontal dimension that matters. However, for professional selection, the Distance Between Uprights is often more critical.

The table length defines how wide a sheet you can bend, but the distance between the side frames determines if a part can “pass through” to the back of the machine. If you are fabricating 3-meter panels that require multiple bends across their depth, but your uprights are only 2.6 meters apart, you will be physically unable to slide the part through. Always choose a machine where the distance between uprights is at least 10% wider than your longest workpiece to ensure operational flow.

3. Throat Depth: Overcoming Flange Height Limitations

The Throat Depth is the C-shaped gap in the side frames, and it is a specification that directly impacts your ability to create complex shapes. From a user’s perspective, this parameter dictates the maximum depth of a flange that can be bent across the full length of the machine.

If you are bending a U-profile with a deep side flange, that flange must be able to sit inside the “throat.” If your flange is 500mm deep but the machine only offers a 400mm throat, the plate will strike the frame before the bend is completed. For custom CNC bending services, prioritizing a deeper throat depth provides the versatility needed to handle architectural panels and large-scale enclosures.

| Bending Force | Ton |

| Bending Length | mm |

| Distance Between Columns | mm |

| Stroke | mm |

| Max Open Height | mm |

| Throat Depth | mm |

4. The Vertical Envelope: Ram Stroke and Max Open Height

These two Press Brake Technical Specifications must be analyzed as a single system. Max Open Height (Daylight) is the total vertical window, while Ram Stroke is the actual movement range of the upper beam.

For a customer, this synergy determines “Box Depth.” You need enough stroke to bring the punch down to the die, but you also need enough open height to lift the punch high enough to remove a deep, finished box from the machine. When selecting a machine, always calculate your Press Brake Tooling Clearance: subtract the height of your upper punch and lower die from the open height; the remaining space must be larger than your deepest part to ensure it can be safely removed.

5. Bending Speeds: Balancing Productivity and Precision

A professional spec sheet will list Approach, Working, and Return speeds. In high-volume production, these numbers translate directly to your hourly output. High approach speeds reduce idle time, while a controlled working speed is essential for maintaining angle accuracy and operator safety.

For shops focusing on mass production, faster hydraulics are a priority. However, if your work involves high-precision electronic enclosures or aerospace components, look closer at Ram Repeatability (typically ±0.01mm). Speed is a commodity, but repeatability is the foundation of quality.

6. Multi-Axis Backgauge: Handling Geometric Complexity

The backgauge is the “brain” of part positioning. While an X-axis (depth) is standard, a professional buyer must consider the R-axis (height) and Z1/Z2-axes (lateral movement).

If your parts involve multiple steps with different flange heights, an R-axis is non-negotiable—it allows the backgauge fingers to move up and down to meet the part. Independent Z-axes allow for asymmetrical bending. Investing in a 4-axis or 6-axis CNC Backgauge may have a higher upfront cost, but it eliminates hours of manual adjustment, making your metal fabrication equipment significantly more profitable.

4+1 Axis Press Brake versus 6+1 Axis Press Brake Which Is Right for You